How Elite Performers Create The "Magic"

Jun 21, 2017

Athletes call it “the zone”. Fans call it “clutch”. Creatives call it “the flow state”. It’s something that really can’t be described, only observed. It can’t be forced, but only slipped into.

Michael Jordan in Game 6 of the NBA finals, clutch. Tom Brady, down 28-3 in the Super Bowl, clutch. As good as LeBron James is, his reputation of being clutch throughout his career has been challenged by many observers of the game, perhaps until the 2016 NBA Finals and a clutch chase down block.

Although we can’t create them, we recognize these moments for what they are when they happen. Their transcendent, Hollywood nature that perhaps can only be summed up with one word…

Magic.

There’s a fine line between great and world class. It’s called clutch.

What we can’t do very well is grasp how and why they happen. What is it that makes clutch performers different from all other elite performers? The Atlanta Falcons were an elite team, but Tom Brady and the Patriots were clutch. The Utah Jazz had two of the NBA’s 50 Greatest Players in their lineup, but MJ and the Bulls were clutch.

How are some seemingly always able to rise the occasion, to steal glory from the grasps of another in clutch moments, almost like they were born for those moments, while others choke?

Those who choke, we label as not being able to "finish" or lacking that “killer instinct.” Is that fair?

What separates the clutch from the chokers?

Simply asked, how and why are clutch performers able to create the magic?

Magic Moment

At the end of Game 1 of the 1995 NBA Finals, my hometown team the Orlando Magic held a 3 point lead over the Houston “Clutch City” Rockets with just 10 seconds left in the game. Magic guard Nick Anderson was at the free throw line for two shots. All he had to do was make 1 of the 2 and the Magic would clinch the game.

Anderson stepped up to the line, dribbled the ball a couple times, took a deep breath and… missed the first shot.

Again, he stepped up to the line, dribbled the ball a couple times, took a deep breath and…missed the second the shot.

BUT…he was fortunate enough to get the rebound and was fouled again. Two more attempts, this time with 7 seconds remaining. All he had to do is make one.

He missed the first.

He missed the second.

The rest goes as expected. The Clutch City Rockets bring the ball down the court and hit a game tying three pointer to send the game into overtime, before winning it in OT.

Anderson would never recover. The career 74% free throw shooter before the debacle, would go on to shoot only 40% the rest of his career, earning the nickname Nick “The Brick” Anderson. “It affected the way I played,” he said. “It affected the way I lived. It played in my head like a recorder – over and over again.”

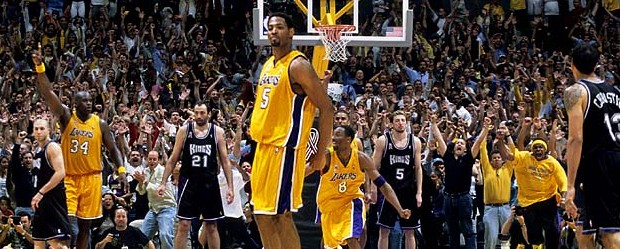

One of Anderson’s opponents on the Rockets that night was Robert Horry. In weird twist of opposing storylines that only sports can provide, Horry built a career on clutch, earning himself the nickname “Big Shot Bob.” Horry had 7 notable clutch shots at the end of games in the playoffs throughout his career. Time and time again delivering the magic when the lights were shining brightest.

One career ruined by an epic failure in the clutch, another made by it. Was “Nick The Brick” just unlucky and “Big Shot Bob” lucky? Or was there a psychological or physiological factor at play that caused one to choke and the other to always deliver in the clutch?

“I Don’t Really Remember Anything”

If you’ve ever personally experienced a moment in the zone or flow state, you walked away from it saying the same thing everyone else says – “I don’t really remember anything.”

North Carolina Psychologist Dr. Dan Chartier sees this a lot in his work treating PTSD victims and as well with athletes. Chartier tells the story of a North Carolina state trooper who came upon a disoriented man standing by his wrecked car late one night on the highway.

Since the man wasn’t being charged with anything, the trooper let the man ride in the front seat as he gave him a ride. During the ride, they were going about 60 mph when the man mumbled something like “they are telling me I have to kill you” before lunging for the officer and wrapping his hands around the officer’s throat.

Somehow, in a clutch performance, the officer managed to grab his gun and shoot the man while safely maintaining control of the high-speed vehicle.

Chartier says he’s heard hundreds of similar stories. Stories of survival and triumph all ending with the survivor saying they don’t remember it.

They just went into automatic.

Thinking vs. Doing

We see this in athletes too. If you’ve ever listened to an athlete talk about their clutch performance in the post-game press conference, often they don’t consider themselves clutch at all.

Dr. Michael Gervais, a prominent sports psychologist in California, says that “Clutch is often defined by observers more so than by doers. If an athlete is thinking it’s clutch, they’ve probably made it too big, and they’re thinking rather than doing.”

And here we come to the core of it all: the more one thinks about being clutch, the less likely it is to come to pass.

Most of us get hung up in clutch moments. We’re so focused on the outcome that we can’t shut it off. We can’t execute because we’re thinking about what it would mean to win the account, the amount of revenue, the public recognition, or conversely the embarrassment that would come by losing it.

Elite producers who rise to the moment, knowing every nuanced move to make and word to say, are able to shut their mind off by detaching their thoughts from the outcome. It’s the same thing athletes do, shut if off.

This is why, after moments of transcendence, we can hardly remember them, much less articulate them.

“Hypofrontality” Phenomenon

There is actually a scientific term for this phenomenon called “hypofrontality,” wherein the part of the brain responsible for critical, analytical thinking – the frontal cortex – shuts down almost entirely. That’s when the magic happens.

Instead of thinking, you’re just doing.

Technology exists, called EEG, that can measure this. There are parts of our brain responsible for thinking – generally found on the left side of the brain, parts responsible for feeling – generally in the middle, and parts responsible for doing – generally found on the right.

Researchers using EEG have found that, in the flow state, the thinking parts shut down and the feeling and doing parts fire up.

In the frontal cortex is where our Imposter Syndrome, or inner critic, is housed. The part of our brain that is always finding something wrong with what we’re doing.

When the frontal cortex shuts down when we enter into flow, our inner critic shuts up with it.

Instead of thinking about the outcome or judging the process, we just do.

Slipping Into The Flow State

But here’s the catch – slipping into flow state is not easy. The harder one tries, the less likely it is to actually happen.

Perhaps another way to better understand what triggers clutch is to look at the opposite of clutch – choking – and what causes it.

Going back to “Nick The Brick’s” comments on his epic choke, “It played in my head like a recorder – over and over again.”

The root cause of choking is fear. In moments of extreme pressure, when the lights are shining brightest and the stakes are highest, fear is what hijacks most of us.

Drowning Out the Noise

The temptation when facing a clutch moment is to think about how great it would be to do well in that moment – or, more likely, how awful it would be to do poorly. For athletes in an arena, they call this “drowning out the noise.”

One of the toughest places for an athlete to drown out the noise is standing on the free throw line at the end of a game. Play is stopped. Everybody in the arena is watching you. The external noise is loud, but the most deafening noise is the one screaming inside your frontal cortex.

And it is screaming fear.

There is one great truth that eliminates fear and creates the magic.

The Big, Beautiful, Impossible Secret to Creating the Magic

Back to the story about the state trooper for a second. He told Chartier “My training just took over.”

Did you know that a majority of Michael Jordan’s game winning shots were from roughly the same spot of the court? A spot he consistently practice shooting from in practice. And “Big Shot Rob’s” game winners were all from the same distance.

Based on his work, Chartier believes “The cornerstone of clutch play is training. You can’t do these things if you haven’t spend a lot of time training basic skills.”

Not just training in the sport, but training in the sport’s most stressful moments. And then come clutch time, it’s all about shutting it off and trusting that training.

Alabama football coach Nick Saban is famous for what he calls “The Process.” When asked, after winning the National Championship, why his teams always seem to come through in the biggest clutch moments, he responded by saying it’s because they coach the players not to worry about the outcome - only the process. They don’t let their team think about the outcome, but just to focus on doing their job for the next play. To “trust their training.”

Which brings us to the big, beautiful, impossible secret to creating the magic – elite-level training.

In clutch moments, if you are thinking about being clutch, most likely you will not be. You need to shut if off, and trust your training, and just do.

One of the primary parts of the brain that goes quiet during a clutch performance is the neocortex. Birds and reptiles don’t even have one. This is what allows humans to think so complexly. It is also what allows us to imagine the future and be aware that we are “someone.”

When this shuts down, we forget about ourselves. As author Brandon Sneed puts it, “When we can do this, we transcend not only our own thoughts and fears, but also, the very concept that we are some sort of special individual at all. When you are clutch, you are great because you are forgetting about yourself.”

Friend, if you want to perform at the highest of your human limits, the trick is being able to forget you’re even human at all - and just...be.

Your level of training will determine the magic you create.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Cras sed sapien quam. Sed dapibus est id enim facilisis, at posuere turpis adipiscing. Quisque sit amet dui dui.

Stay connected with news and updates!

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.